Episode 6

Tibial Plateau Fractures & Orthopaedic Emergencies

Listen to Episode:

Objectives:

After this episode, we hope that you are able to:

- Perform a detailed history and physical examination for tibial plateau fractures.

- Explain the classification system for tibial plateau fractures.

- Understand the fundamentals of the surgical approaches and fixation techniques for tibial plateau fractures.

- Understand the diagnostic and management strategies for compartment syndrome and open fractures.

Show Notes

Episode 6:

Tibial Plateau Fractures & Orthopaedic Emergencies

What is the Gustillo-Anderson classification of open fractures?

The Gustilo-Anderson classification is a widely used system for categorizing open fractures, primarily based on the mechanism of injury, wound size, degree of soft tissue damage, and the presence of contamination. This classification helps guide treatment decisions and predict outcomes. For a full overview of this classification system, check out the dedicated

Orthobullets page, however, we will provide a brief overview of the key points here.

Type I

Wound less than 1 cm in length (sometimes referred to as a “poke-hole”) with minimal contamination and muscle damage. These wounds can be very small; however, the size and nature of the wound may not reflect damage to the deeper structures. As such, it is important to examine the overlying soft tissue very closely. Wounds with a continuous ooze are always more suspicious, however, any soft tissue wound in proximity to a fracture should be treated as open fracture until proven otherwise, as it can lead to infection and other complications if not properly managed.

Type II

Wound size of 1-10 cm and are associated with moderate soft tissue injury.

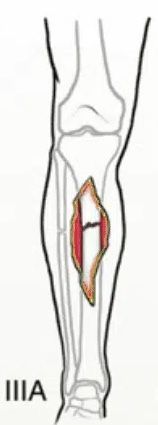

Type IIIA

Wounds usually larger than 10 cm, indicating high-energy trauma with extensive soft-tissue damage and contamination. Despite the severity, there is adequate tissue available for flap coverage, making surgical reconstruction feasible. Farm injuries, due to their high contamination level and potential for severe tissue damage, are generally classified as at least Gustillo IIIA.

Type IIIB

Wounds usually larger than 10 cm. These fractures are marked by extensive soft tissue damage and periosteal stripping. Interventions for soft tissue coverage, such as rotational or free flaps, are typically required.

Type IIIC

Distinguished by the presence of a vascular injury that requires repair, regardless of the degree of soft tissue injury.

Images from RebelEM.

Importantly, the most accurate method to grade open fractures is through intra-operative examination. This approach allows for a thorough assessment of the wound's depth, the extent of soft tissue damage, and contamination level that may not be fully appreciated pre-operatively.

The infection rate for open fractures also varies significantly based on the Gustilo classification. Infection rates are estimated to be 0-2% for Type I open fractures, 2-10% for Type II fractures, and significantly higher at 10-50% for Type III fractures. [JAAOS 2010;18:108-117].

Which antibiotics should be used for open fractures?

The choice of antibiotic prophylaxis for managing open fractures is tailored according to the Gustilo classification and the level of contamination, as detailed on

OrthoBullets.

For Gustilo Type I and II fractures, a 1st generation cephalosporin such as Cefazolin is recommended, with Clindamycin or Vancomycin as alternatives for patients with allergies. In the case of Type III fractures, the antibiotic regimen is escalated to include Cefazolin plus an aminoglycoside (e.g., Tobramycin or Gentamycin) to cover a broader spectrum of bacteria.

Special considerations are also given to wounds incurred in specific environments. For injuries sustained in a farm environment, heavy contamination, or those with potential bowel involvement, adding high-dose Penicillin is advised for enhanced anaerobic coverage, specifically against Clostridium species.

Freshwater wounds, which may expose the patient to

Aeromonas hydraphila, warrant the addition of Fluoroquinolones or a 3rd or 4th generation cephalosporin (e.g., Ceftazidime). Saltwater wounds, at risk of infection by

Vibrio species, should be managed with Doxycycline in combination with Ceftazidime or a Fluoroquinolone. These tailored antibiotic strategies are crucial for preventing infection and promoting optimal healing outcomes in patients with open fractures, considering the specific risks associated with the mechanism of injury and environmental exposure.

What are the considerations for tetanus prophylaxis in the management of open fractures?

Tetanus prophylaxis plays a critical role in the management of open fractures due to the potential contamination of wounds with

Clostridium tetani, which is ubiquitous in the environment. Open fractures provide a direct portal of entry for

Clostridium tetani into the body, bypassing the skin's role as a primary barrier against infection. Once in the body, C. tetani can produce a potent toxin, tetanospasmin, leading to tetanus, a serious condition characterized by muscle rigidity and spasms. Tetanus is a potentially life-threatening condition. Prophylaxis is crucial because once symptoms appear, the disease is difficult to manage and has a high morbidity and mortality rate.

When assessing a patient with an open fracture, their immunization history against tetanus should be reviewed promptly. For patients with an unknown or incomplete vaccination history, or those who have not received a tetanus booster recently, a tetanus toxoid-containing vaccine is indicated. The management of these patients with regards to tetanus status depends both on their immunization history and the classification of their wound, which can be summarized in the table below [from

OrthoBullets]:

| Immunization History | Gustillo-Anderson Grade I | Gustillo-Anderson Grade II-III |

|---|---|---|

| Unknown history or <3 doses | Give vaccine only. | Give vaccine and immune globulin. |

| Vaccination complete (3 prior doses) | No prophylaxis if last dose within 10 years. Give vaccine if >10 years since last dose. | No prophylaxis if last dose within 5 years. Give vaccine if >5 years since last dose. |

In terms of the vaccine, tetanus toxoid booster (Tdap or Td) is recommended for patients with minor wounds (GA grade I) who have an unknown immunization history or less than 3 doses, as well as those patients with complete tetanus vaccination who have not received a booster in the last ten years. In patients with larger wounds (GA grade II-III), the vaccine should be given in patients with a complete vaccination history who have not received a booster dose in the last 5 years. Tetanus immune globulin (TIG) may also be given with the vaccine in these larger wounds, if their immunization status is incomplete or unknown. Of note, toxoid and immunoglobulin should be given intramuscularly with two different syringes in two different locations.

Administration of tetanus prophylaxis should occur as soon as possible after injury, ideally within the first few hours, to maximize effectiveness. In keeping with the general principles of open fracture management, proper wound care, including thorough irrigation and debridement, is also essential in reducing the risk of tetanus and other infections.

What is the underlying physiology of compartment syndrome?

Compartment syndrome occurs when increased pressure of a myofascial compartment results in insufficient blood supply to tissue within that space. The underlying physiology involves a cycle of increasing pressure and decreasing perfusion that ultimately leads to tissue ischemia and cellular death if not promptly treated.

The compartments in the limbs are enclosed by fascia and bone, creating relatively inelastic spaces. When pressure within a compartment increases, it compresses vessels, nerves, and muscles. The initial increase in pressure can be due to external factors (such as tight casts) or internal factors (such as hemorrhage or edema from trauma or burns). As pressure increases, venous outflow is obstructed, leading to venous congestion and a further increase in compartment pressure. This venous congestion reduces arterial inflow, exacerbating ischemia. The critical pressure threshold at which blood flow is compromised varies among individuals but is generally considered to be greater than 30 mmHg. The definition of >30 mmHg difference between the diastolic blood pressure and the compartment pressure is also used, as this is the pressure required to obstruct venous outflow. Ischemia within the limb leads to cellular death and the release of toxic metabolites, which further increases capillary permeability and edema, creating a vicious cycle. If the pressure is not relieved by urgent fasciotomy, it can result in permanent damage to nerves and muscles.

In the episode, you learned out the “P’s” of compartment syndrome. Think back to these cardinal symptoms, and try to relate each one to the underlying physiology. Then, click to reveal the answers.

We can relate the underlying physiology of compartment syndrome back to the P’s of compartment syndrome that you learned about in the episode:

- Pain out of proportion: The earliest and most significant sign! Pain that is severe and not relieved by analgesics or elevation arises from the combination of ischemia and the pressure on nerves within the compartment.

- Pain with passive stretch: Stretching the muscles within the affected compartment further increases the intra-compartmental pressure, exacerbating the pain. This sign is particularly sensitive to the diagnosis of compartment syndrome because it directly relates to the mechanical effect of increased pressure on muscle groups.

- Palpable firmness: This sign refers to the increased firmness of the affected compartment when palpated. This characteristic is a direct result of edema, muscle swelling, and the incompressible nature of the fascial boundaries encasing the compartment. Palpable firmness can often be detected early in the course of compartment syndrome and serves as a tangible indicator of the underlying pathophysiological processes.

- Poikilothermia: This term refers to the affected limb becoming cooler than the rest of the body, resulting from reduced blood flow and, consequently, decreased tissue warmth.

- Pulelessness: This is a late and ominous sign indicating a severe reduction in arterial blood flow to the affected limb.

- Proprioception loss: Increasing numbness, tingling, or loss of sensation occurs due to nerve ischemia and pressure-induced nerve damage within the compartment. Early signs might include a sensation of pins and needles, progressing to total sensory loss if untreated.

- Pallor: The skin may appear pale due to the reduced blood flow to the affected area. However, pallor is a less reliable sign and may not be evident in all cases of compartment syndrome.

What is the ATLS algorithm, as an approach to a trauma patient?

The

Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) algorithm offers a systematic framework for managing trauma patients, who often present with injuries from high-energy mechanisms with potential for catastrophic outcomes. The protocol includes the assembly of a multidisciplinary trauma team, encompassing specialties such as orthopaedic surgery, general surgery, anesthesia and nursing, among others. Each team member plays a distinct role and adheres to specific priorities following trauma team activation. This discussion will concentrate on the responsibilities of the orthopaedic surgery attending or resident. Understanding the orthopaedic surgery team’s function within the ATLS context is crucial, especially as you may encounter a trauma team activation during your rotation.

ATLS provides a systematic approach to the assessment and treatment of trauma patients. It emphasizes the importance of treating the most life-threatening conditions first, following the principle of "treat first what kills first." The primary survey, resuscitation, secondary survey, and definitive care are the four key components of the ATLS algorithm:

- Primary Survey: Follows the ABCDE approach to identify and manage immediate life-threatening injuries.

- Resuscitation: Addresses physiological disturbances identified during the primary survey, focusing on stabilizing the patient's airway, breathing, circulation, and preventing hypothermia.

- Secondary Survey: A thorough head-to-toe examination and patient history collection, performed after life-threatening injuries have been addressed, to identify all injuries.

- Definitive Care: Involves the surgical or medical management of injuries, rehabilitation, and follow-up care.

The primary survey follows the ABCDE approach to quickly identify life-threatening conditions. Below, we will briefly go through each section, with a specific focus on the role of the orthopaedic surgery team within each step in the algorithm.

A - Airway + C-Spine

A is for airway management. It’s crucial to ensure that the airway is open and clear, a task primarily managed by anesthesia and respiratory therapy teams. However, the orthopaedic team plays a critical role in cervical spine (c-spine) protection. This includes ensuring the placement of a cervical collar, particularly in patients with high-energy trauma mechanisms, to safeguard against potential unstable c-spine injuries that could lead to spinal cord injuries and neurological deficits. Furthermore, during situations where intubation is necessary and a cervical collar may impede the process, the orthopaedic team may be called upon to manually stabilize the patient's neck, ensuring both effective airway management and c-spine protection simultaneously.

B - Breathing

B is for breathing. The role of the orthopaedic team, while often supportive, remains important. The primary objective is to assess and manage any breathing problems, specifically identifying issues such as chest wall instability, flail chest, pneumothorax, or hemothorax. While the responsibility for addressing these conditions typically falls to other members of the trauma team, it's crucial for the orthopaedic team to be adept at recognizing these injuries. Their ability to identify and, when necessary, assist in the management of such conditions can be instrumental in stabilizing the patient and preventing further respiratory compromise.

C - Circulation

C is for circulation. In this component of the primary survey, the orthopaedic team plays a critical role in managing conditions that could lead to significant bleeding and hemodynamic instability. Orthopaedic injuries, such as pelvic and long bone fractures, are prime examples where orthopaedic intervention is essential.

Pelvic stability assessments are pivotal in the initial evaluation of trauma patients, especially given that pelvic injuries can lead to substantial blood loss and hemodynamic collapse. The assessment involves specific maneuvers to identify types of pelvic instability—internal rotation (IR) forces applied to the iliac wings can reveal IR instability (lateral compression or LC injuries), external rotation (ER) forces can indicate ER instability (anterior-posterior compression or APC injuries), and traction to the leg or vertical forces can identify vertical instability. An anteroposterior (AP) pelvis radiograph is recommended for all polytrauma patients or those with hemodynamic instability following a traumatic mechanism of injury.

The use of a pelvic binder or sheet is a critical intervention by the orthopaedic team in the trauma bay to temporize injuries. The primary goals of applying a pelvic binder or sheet include closing the volume of the pelvis to reduce space for potential bleeding, stabilizing clots on bony surfaces and vascular structures, and providing temporary stability. This intervention is particularly indicated for pelvic ring injuries accompanied by hemodynamic instability, highlighting the orthopaedic team's role in acute management to improve resuscitation outcomes and prepare patients for definitive surgical care.

D - Disability

D is for disability. In this phase of the primary survey, the focus shifts to evaluating the neurological status of the trauma patient. The orthopaedic team has a dual role during this stage. While other members of the trauma team use the AVPU scale (Alert, responds to Verbal stimuli, responds to Painful stimuli, Unresponsive) or the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) to assess the patient's consciousness and neurological function quickly, the orthopaedic team concurrently performs a meticulous examination of the extremities. This involves identifying any limb injuries that may impact the patient's neurological status or overall outcome. Detecting extremity fractures, dislocations, and soft tissue injuries is crucial for planning further management, and it also contributes to the overall assessment of the patient's disability status.

E - Exposure

E is for exposure. This component of the primary survey mandates the complete removal of all clothing to ensure a thorough examination and to avoid missing any injuries. For medical students involved in trauma care, being proactive by locating trauma shears before the patient's arrival can be a practical contribution to the team, facilitating rapid and efficient patient exposure.

Once the patient is fully exposed, a log roll maneuver is performed to assess the integrity of the spine. The orthopaedic team's role here includes a meticulous spine assessment with a systematic approach:

- Look for any wounds, contusions, or deformities along the spine.

- Feel for abnormalities along the spinal column by palpating the spinous processes from the cervical to the lumbar spine. The team assesses for any steps or gaps between vertebrae, any bogginess or crepitus that might suggest an underlying fracture or injury, and areas of tenderness that the patient may express.

- Perform DRE (Digital Rectal Examination) to assess for sacral sparing, which includes checking for sensation, motor function (such as active or passive rectal tone), presence of blood, or a high-riding prostate, which can indicate a serious pelvic injury.

Secondary Survey

During the secondary survey, the orthopaedic team conducts an extensive assessment of the patient's extremities, which is essential after life-threatening injuries have been addressed. This detailed evaluation begins with a full 360-degree inspection for any open wounds, including the perineum. The team also looks for gross deformities that may be fractures or joint dislocations and palpates all bones for signs of tenderness or subtle deformities. Joint integrity is assessed through both active and passive ranges of motion, and each joint is stressed to check for instability.

A comprehensive neurovascular examination is also performed, encompassing both myotome and dermatome patterns, evaluation of peripheral nerve function, and a vascular assessment that includes checking for the presence and quality of pulses, as well as observing skin color, temperature, and capillary refill time.

Imaging also plays a pivotal role, with X-rays obtained for any suspected injuries. The timing and prioritization of imaging are critical decisions based on the patient's overall condition and the likelihood of injury. Once injuries are identified, the orthopaedic team moves swiftly to manage them. Wound care may involve irrigation and debridement, and temporary or definitive closure techniques. Reductions of dislocations and fractures are performed to re-establish normal anatomy and relieve pain, followed by the application of splints to immobilize the affected area until definitive surgical treatment can be performed. This thorough process ensures that no injury is missed and that all are managed effectively to promote the best possible outcome for the patient.